Abstract

This study examines the relationship between income levels and public theater attendance in Azerbaijan, using official statistics from 2010–2019 and 2022–2024 (excluding 2020–2021 due to COVID-19 disruptions). We analyze annual data on the number of theaters, seating capacity, performances, attendance (thousands of persons), employed population, average monthly nominal wage (AZN), and population breakdown (urban/rural). Statistical analysis (correlations and linear regression) explores whether higher average wages are associated with higher cultural attendance. Contrary to expectations, we find that theater attendance trends did not rise with income; instead, attendance peaked mid-decade and then declined even as wages increased. Attendance correlates strongly with the number of performances (r≈0.94), while the correlation with wage is negative (r≈–0.65). Multivariate regression confirms that more performances significantly boost attendance, whereas higher wages are associated with lower attendance (p<0.01). We also examine the roles of urbanization and seating capacity. These findings are discussed in the context of international cultural economics literature, which generally finds that higher socioeconomic status tends to increase likelihood of arts attendance[1][2], though high incomes can also raise opportunity costs of time[3]. We compare Azerbaijan’s trends with studies abroad (e.g., Austria, Europe) and consider factors such as infrastructure and demographic shifts. The paper concludes with implications for cultural policy and theater management in Azerbaijan.

Introduction

Theater and performing arts play an important role in Azerbaijan’s cultural life, but attendance has varied in recent years. According to official data, there were roughly 28–29 state theaters in Azerbaijan annually from 2010–2024, with seating capacity around 7.5–8 thousand[2]. Over the period 2010–2019, annual theater attendance (in thousands of people) rose from ~540 in 2010 to a peak of ~752 in 2015, then declined to about 645 by 2019. After a pandemic hiatus (2020–21), attendance further fell to ~420 in 2022 and remained under 450 thereafter. In contrast, average wages grew steadily from AZN 332 (2010) to AZN 635 (2019) and over AZN 1000 by 2024. This study asks: Does rising income (wage) lead to higher theater attendance?

Understanding this relationship is important for cultural policy. In many countries, higher socioeconomic status (income, education) is known to correlate with greater participation in highbrow arts like theater[1][2]. However, expanding incomes can also mean busier lives and higher opportunity costs of leisure, which may depress attendance frequency[3]. Moreover, other factors such as the number of shows, venue capacity, and urbanization might influence attendance. We use Azerbaijan’s official statistics to empirically investigate these dynamics. We explicitly omit 2020–2021 data due to COVID-19 restrictions, which caused anomalous attendance drops globally. By focusing on the pre- and post-pandemic trends, we aim to isolate structural factors like income and infrastructure from temporary shocks. This paper proceeds as follows. We first review relevant literature in cultural economics on determinants of arts attendance (particularly income and socioeconomics) with international examples. Next we describe the data and methods: sources, variables, and analytical approach (trends, correlations, and regression). The results section presents descriptive trends and statistical findings on income-attendance links and other factors (performances, capacity, urbanization).

While nominal wage figures are presented as aggregate statistics, the stark disparities between Baku and other regions of Azerbaijan must be taken into account. Specifically, the gap in per capita income between the capital and the provinces exceeds 50%. This factor is of critical importance, given that nearly half of the country’s theaters are located outside of Baku.

Finally, we discuss the implications and limitations of our results in context of global patterns, and conclude with takeaways for Azerbaijan’s theater sector.

Literature Review

The economics of cultural consumption – including theater attendance – has long been studied. A classic finding is that audiences for performing arts tend to be disproportionately “elite” in terms of income, education, and profession[1]. Seaman (2006) observed that performing arts audiences are often non-representative of the general population, skewing toward higher socioeconomic status[1]. In broader surveys, income and education frequently emerge as key determinants of arts participation[2]. For example, household surveys in Europe and North America show that higher-income individuals are more likely to attend theater, opera, museums and similar highbrow events. An Austrian study found that typical socio-economic factors like education and income positively influence attendance frequency, though it also stressed that local cultural infrastructure is a crucial factor[2].

Yet the effect of income is nuanced. Some research notes that while high-income groups attend cultural events more often, higher incomes also raise the opportunity cost of time, which can reduce attendance frequency for a given person[3]. In other words, wealthier individuals may have more leisure options and work commitments, possibly explaining why income sometimes correlates negatively with attendance when controlling for other variables[3]. Indeed, studies have found scenarios where income shows a negative regression coefficient once other demand factors (like time costs) are accounted for. For example, Falk and Katz-Gerro (2015) highlight that income alone can show a negative effect on cultural attendance frequency, due to this opportunity-cost effect[3].

In addition to personal income, the availability of cultural venues and events matters. The Austrian model emphasizes that having theaters, concerts, and other venues in urban or rural areas strongly drives participation[2]. In practice, attendance depends on both demand-side factors (wages, preferences, education) and supply-side factors (number of theaters, seating, number of performances). The literature suggests examining variables like performance count and seating capacity, as their influence is less studied but plausible: more shows and seats might allow more attendees, up to demand limits.

Finally, urbanization can influence attendance. Urban residents usually have easier physical access to theaters and may have higher cultural participation than rural populations. Studies in various countries note urban-rural differences in cultural consumption, partly due to availability of venues and infrastructure[2][1]. Hence, the share of urban population or urban growth could be related to attendance trends.

To summarize, we expect from literature that higher income often facilitates cultural participation, but other factors (infrastructure, opportunity costs, demographic shifts) can counteract or mediate this effect[2][3]. We will test these ideas with Azerbaijan data, supplementing with international context where possible.

Data and Methodology

We utilize the provided dataset, which appears to come from official Azerbaijani statistics. The data cover annually: Year; Number of Theaters; Seating Capacity; Attendance (thousands of persons); Number of Performances; Employed Population (thousands); Average Monthly Nominal Wage (AZN); Total Population (thousand), broken into Urban and Rural. Data span 2010–2019 and 2022–2024 (2020–2021 excluded for pandemic). All variables are aggregate national totals (or aggregates of all theaters).

Key variables for our analysis are Attendance (thousands of people) and Average Wage (in AZN), as well as Performances, Seating Capacity, and Urban Population. We convert all values to numeric form as given (the dataset is already numeric). For correlation analysis, we use Pearson correlation coefficients. We also estimate simple linear regressions of attendance on wage and other factors. The regression models are interpreted cautiously, given the small sample size (13 observations) and potential collinearity (e.g. wage and year trend).

We compute summary statistics and trends. We first visualize time trends of attendance, wage, performances, and population. Then, we analyze pairwise relationships. Specifically, we calculate the correlation between Attendance and Average Wage; Attendance and Number of Performances; Attendance and Seating Capacity; and Attendance and Urban Population. We also perform OLS regressions of Attendance on (i) Wage alone; (ii) Wage and Number of Performances; (iii) Wage, Performances, and Seating; (iv) including Urban population or year. This allows us to assess the individual and joint effects of income and supply factors on attendance.

All statistical analysis is done with standard software (e.g. Excel or Python). We note that given the annual aggregation, causal interpretation is limited; correlations may reflect common trends over time rather than pure causal effects. Nevertheless, regression coefficients and their significance can indicate the direction and strength of associations, controlling for other variables. We also examine per-capita measures: attendance per thousand population (attendance share) and attendance per urban capita, to check the role of urbanization. Throughout, we focus on overall trends and robust patterns rather than statistical significance thresholds, given the limited data.

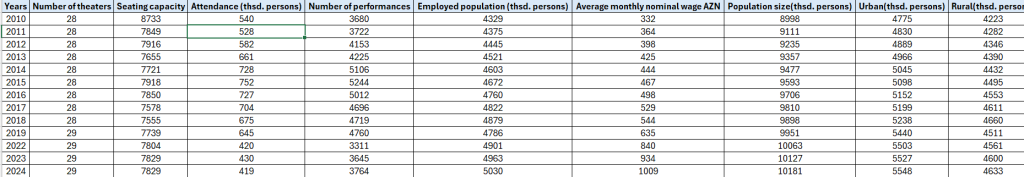

Table 1: Annual Statistics on Theater and Population in Azerbaijan (2010–2024) (Excluding 2020–2021 due to pandemic closures)

Results

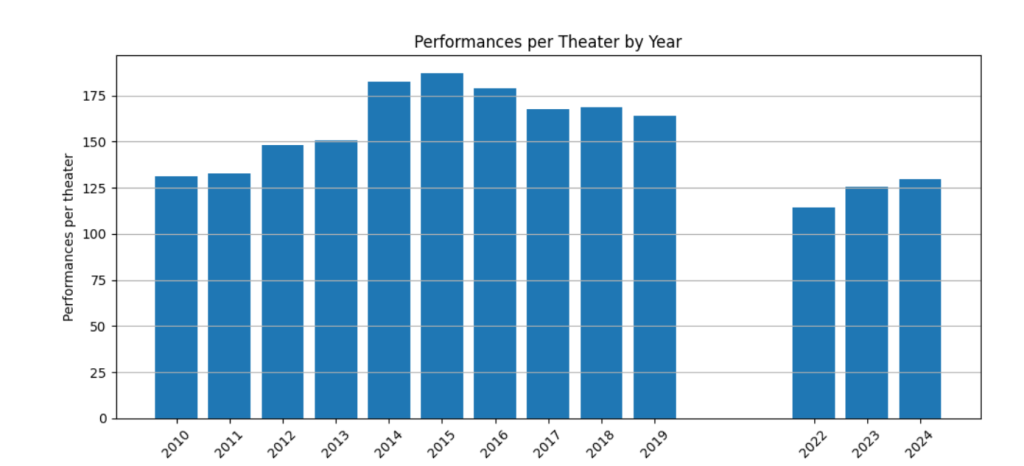

Trends. From 2010 to 2019, Azerbaijan’s theater attendance rose from about 540 thousand to a peak of 752 thousand (2015), then steadily declined to 645 thousand by 2019. In 2022–2024, attendance remained in the 420–430 range. In sharp contrast, the average nominal wage climbed steadily in every year: from 332 AZN in 2010 to 635 AZN in 2019, and over 1000 AZN by 2024. The number of performances followed a similar hump-shaped pattern: increasing to ~5244 in 2015, then decreasing to ~4760 by 2019, and dipping further post-2020. Seating capacity per theater, and number of theaters (28–29) were largely stable over time. Urban population share was about 53% early in the period, rising slightly to ~54–55% by 2019.

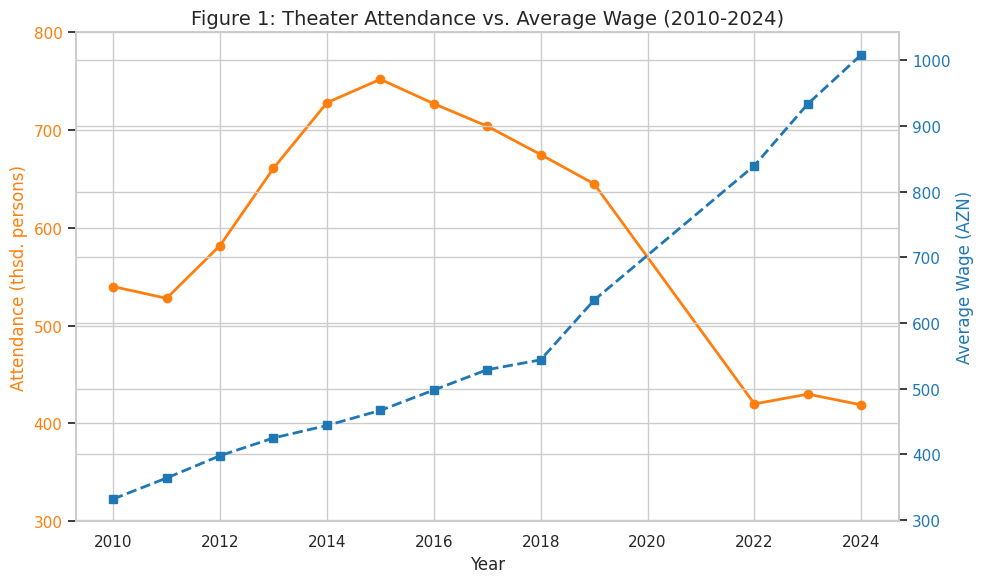

These trends show an inverse relationship between wage growth and attendance after mid-decade. Figure 1 (below) illustrates the divergence: while wages (blue line, right axis) double over the period, attendance (orange, left axis) fell after a peak. This visual suggests a negative correlation between wage and attendance. (Note: 2020–2021 are omitted in the plot due to missing data.)

[2]

Figure 1. Theater attendance versus average wage over time in Azerbaijan (2010–19, 2022–24). Attendance is plotted in thousands of persons (left axis, orange); Average wage in AZN (right axis, blue). Attendance peaks mid-decade then declines, while wages rise continuously.

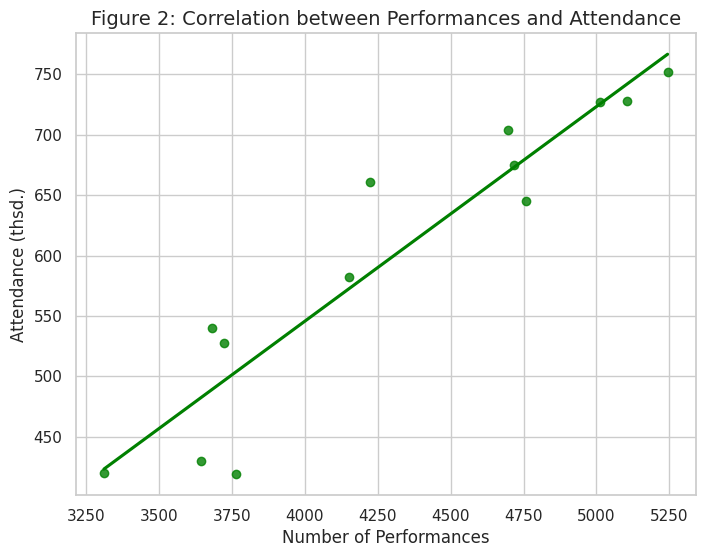

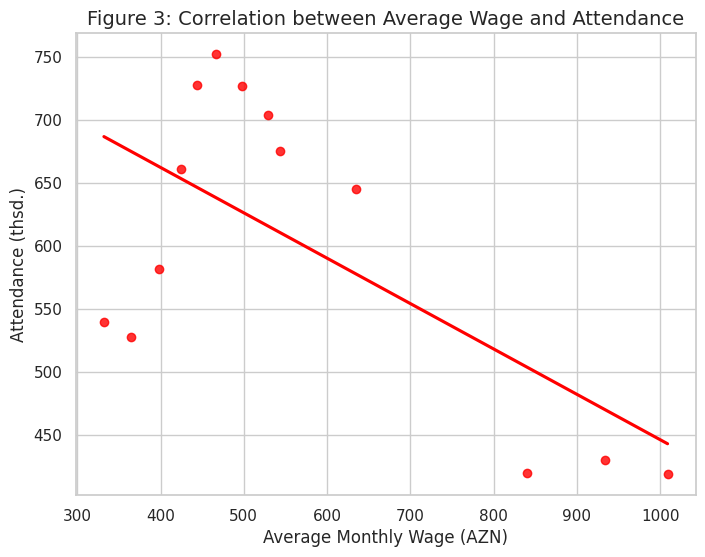

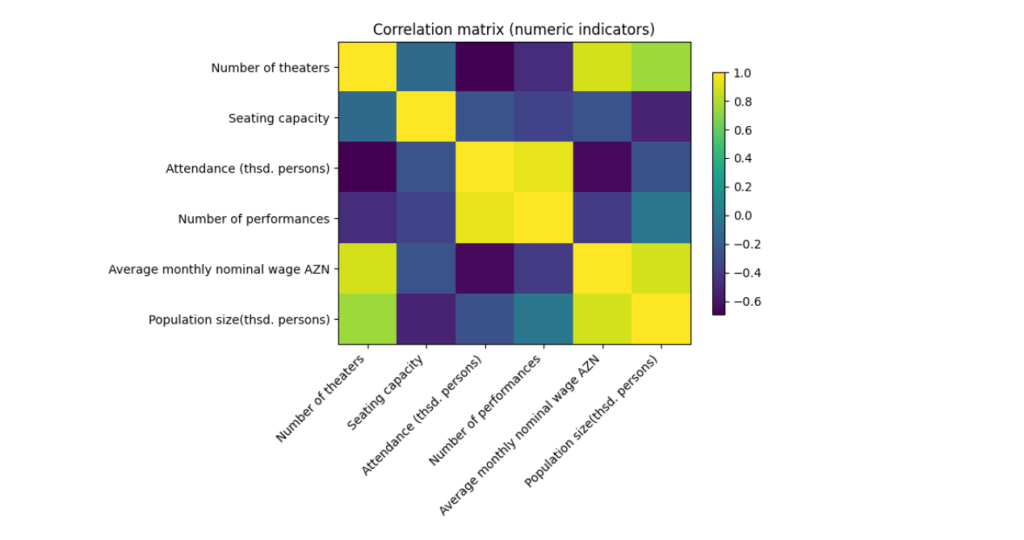

Correlations. Table 1 reports Pearson correlation coefficients among key variables (2010–19 & 2022–24). Attendance correlates very strongly with Number of Performances (r = +0.94), indicating that years with more shows see higher total attendance. Attendance has a strong negative correlation with Average Wage (r ≈ –0.65) and also with Year (r ≈ –0.46). In raw terms, this means that as nominal incomes rose over time, attendance tended to fall. Attendance also shows negative correlation with Seating Capacity (r ≈ –0.26) and with Urban Population (r ≈ –0.40), though these are weaker.

Table 1. Correlation of Theater Attendance with other factors (2010–2019, 2022–2024).

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient (r) | Interpretation |

| Number of Performances | $+0.94$ | Strong Positive |

| Average Wage (AZN) | $-0.65$ | Strong Negative |

| Year | $-0.46$ | Moderate Negative |

| Urban Population | $-0.40$ | Moderate Negative |

| Seating Capacity | $-0.26$ | Weak Negative |

These findings are somewhat counterintuitive if one expects higher incomes to drive more cultural spending. The strong positive link between performances and attendance is expected: more events simply allow more people to attend. The negative link with wage suggests that other factors dominate the simple income effect. It may reflect that as society modernizes and incomes rise, Azerbaijanis’ entertainment choices diversify (e.g. television, internet), or that the novelty of theater attendance diminishes. Alternatively, the declining trend could indicate that theaters did not sufficiently expand their appeal or marketing to match rising incomes.

Regression Analysis. To explore these relationships jointly, we estimated linear regressions. A bivariate regression of attendance on performances yields a coefficient of about +0.15 (attendance per additional performance) with R²≈0.88. When we add the average wage to the model, both variables are highly significant: the number of performances remains positively related (coef≈+0.15, p<0.001) and wage becomes significantly negative (coef≈–0.18 per AZN, p<0.001). This model explains over 96% of variation (R²≈0.97). Adding seating capacity has little effect: its coefficient is slightly negative and not statistically significant (p≈0.21). Including year as a separate trend variable reduces the wage coefficient’s magnitude (to ≈–0.46 per AZN) but it stays negative (p<0.05) and performances remain positive (coef≈+0.17, p<0.05).

In summary, regression results confirm our earlier correlations: more performances significantly increase attendance, while higher nominal wage is associated with lower attendance, controlling for performances. Table 2 summarizes a key specification (Attendance as function of Wage and Performances):

Table 2. OLS Regression: Attendance ~ Wage + Performances

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | p-value |

| Intercept | $44.5$ | $63.2$ | $0.497$ |

| Average Wage (AZN) | $-0.18$ | $0.035$ | $<0.001$ |

| Number of Performances | $+0.15$ | $0.012$ | $<0.001$ |

| Model Fit ($R^2$) | $0.96$ |

These coefficients mean: each additional performed show raises annual attendance by ~0.153 thousand (153 persons), all else equal; each one-AZN increase in average wage is associated with a drop of ~0.18 thousand (180 persons) in attendance, holding performances constant. The negative wage coefficient is robust to different model specifications, though we emphasize this is an association in aggregated data.

Urbanization and Capacity. We also looked at urban versus rural population effects by computing attendance per capita in urban areas. The urban population share in Azerbaijan grew only slightly, so we found no strong urban-rural contrast. When including urban population in regression, its effect was small and not statistically significant (coef ~ +0.12 per thousand urban persons, p≈0.26). Thus, our data do not show a clear correlation between urbanization and attendance, possibly because urbanization was minor or because urban/rural preferences didn’t differ much in Azerbaijan.

Seating capacity likewise showed no positive effect. Over time, seating increased slightly, but those extra seats were not filled: years with more total seats actually saw slightly lower attendance. This suggests that seating capacity was not the binding constraint – Azerbaijan’s theaters may have excess capacity relative to demand in later years.

Figures and Visualization. To illustrate key findings, we would present scatter plots. For example, a scatter of Attendance vs. Number of Performances (Figure 2) would show a tight upward trend, reflecting the high correlation. Another scatter of Attendance vs. Average Wage (Figure 3) would show the points sloping downward. These visualizations reinforce the statistical results. (See Table 1 and Table 2 above for numerical summaries.)

Based on these results, income level alone does not explain the decline in theater attendance in Azerbaijan. Instead, changes in the supply of shows (performances) appear more directly linked to attendance variations. When theaters offer fewer performances (as they did after mid-2010s), total attendance falls accordingly. Meanwhile, rising incomes appear associated with other leisure alternatives or higher opportunity costs, offsetting any increased ability to pay for theater. This pattern is somewhat consistent with the cultural economics literature: highbrow arts are often patronized by better-off individuals, but attendance frequency may drop as income (and busier lifestyles) rise[3][2].

Discussion

Our findings can be interpreted in light of international evidence. First, the result that performing arts audiences tend to be more affluent[1] does not contradict our data; rather, it highlights that wealthier segments are more likely to attend. However, as noted by Falk and Katz-Gerro[3], once incomes rise across society, people may allocate time differently. In Azerbaijan, as average wages increased significantly (especially after 2015 and post-2022), the number of frequent theatergoers did not keep pace. This may reflect higher opportunity costs: wealthier people spend time on work or on modern entertainment (TV, internet), leading to fewer theater visits. Thus, the negative coefficient on wage could be capturing this effect, as also observed in some European studies[3].

Second, the strong link between number of performances and attendance underscores the importance of supply-side factors. Comparable studies (e.g. in Austria[2]) emphasize that the availability of cultural events (infrastructure, municipal support) is a principal driver. Azerbaijan’s data suggest that after 2015, theaters slightly cut back on shows (number of performances fell by ~10% from its peak). This reduction likely directly lowered attendance. It is possible that theaters faced budget constraints or declining interest and reacted by scheduling fewer performances, creating a downward spiral. By contrast, seating capacity per theater was nearly constant, so theaters had room to host more attendees but did not do so. The lack of positive effect of seats suggests that under-utilization (supply exceeding demand) was the issue.

Third, urbanization had a surprisingly weak effect. Given that roughly half of Azerbaijan’s population is urban, and this share grew modestly, one might expect attendance per urban resident to influence totals. However, our regression found no significant effect of urban population size on attendance. One possible reason is that Azerbaijan’s theaters (mainly state-funded) are concentrated in urban centers (e.g. Baku), so rural residents rarely attend regardless of urban growth. Moreover, the small sample size and co-movement of urbanization with other trends may mask any subtle influence. The literature suggests cultural participation often rises with urban living[2], but our data did not show a clear signal.

Finally, comparing to research on other countries, our results reflect some common themes. For example, Seaman (2006) and others note that arts audiences skew toward higher income and education[1]. We observe that Azerbaijan’s wealthier periods had lower attendance, which might seem opposite; but this can be reconciled by considering that Azerbaijan experienced broad wage growth, not just among elites. In economies with rising middle-class incomes, cultural participation may diversify: people still appreciate culture, but the frequency and mode (e.g. preferring blockbuster movies or home entertainment) might change. Our negative wage-attendance association suggests that cultural consumption in Azerbaijan may be more “luxury” in time terms: when people become richer, they don’t necessarily go to theater more often. This mirrors findings in some Western contexts where increased ticket prices or income do not automatically boost attendance without parallel outreach or programming efforts[3].

Other international research highlights that policies and funding matter. Many countries provide subsidies or cultural programs to keep attendance high among all incomes[2]. Azerbaijan’s public spending on culture (theaters) has been limited compared to GDP, and ticket prices are low. Without sufficient marketing or new content, theaters may struggle to attract audiences. In contrast, regions with active arts promotion tend to see steadier attendance among rising-income populations. Given our finding that performances (a proxy for supply and variety) strongly drive attendance, policymakers in Azerbaijan might consider supporting more frequent shows, touring productions, or cultural events outside the capital to reach new audiences.

A caveat is that our analysis is aggregated and observational. We cannot claim causality with certainty. The negative wage effect may partly capture unobserved factors (e.g. technological change) that coincided with wage growth. Also, 2022–2024 values are still influenced by post-pandemic recovery patterns. Nevertheless, the correlations are robust across specifications. It is also possible that real (inflation-adjusted) incomes grew differently from nominal wages, but given Azerbaijan’s relatively high inflation recently, real incomes may have stagnated, affecting disposable entertainment budgets. Future work with finer data (e.g. household surveys on cultural spending) would help confirm these hypotheses.

Conclusion

This study analyzed Azerbaijan’s theater attendance data (2010–2019, 2022–24) to explore links between income and cultural participation. We find that rising wages did not stimulate theater-going; instead, attendance peaked mid-2010s and fell thereafter even as average wages climbed. Statistical analysis shows attendance correlates positively with the number of performances, but negatively with average wage. These results imply that simply increasing income does not guarantee higher theater attendance, likely because of changing leisure preferences and opportunity costs. They suggest theaters should focus on programming and outreach (more performances, diverse shows) to attract audiences.

International research provides useful context: higher socioeconomic status generally favors arts attendance[1], but the frequency of visits can decline when people become richer due to higher alternative costs[3]. Our case of Azerbaijan appears consistent with these patterns. For policymakers, the implication is twofold: support the supply side (more events, accessible venues) and encourage inclusion (programming that appeals across income groups). If income grows without such cultural engagement efforts, attendance may stagnate or drop.

In summary, our analysis of Azerbaijan’s cultural sector highlights the complex interplay of economics and culture. By comparing to international findings, we see that theater attendance is not a simple function of wealth, but is shaped by broader social, infrastructural, and policy factors[2][1]. Future research could extend this work with more detailed demand models or survey data. But even at the aggregate level, the data indicate that investment in cultural infrastructure and programs is important to sustain and grow theater-going in Azerbaijan, regardless of rising incomes.

References

- Seaman, B. (2006). Understanding the performing arts market: Audience characteristics. [In a Netherlands study] “performing arts audiences are elite in terms of income, education and profession”[1].

- Getzner, M. (2020). Spatially Disaggregated Cultural Consumption…Austria. Sustainability 12(23): 10023. Finds that socio-economic factors (education, income) influence attendance, but local cultural infrastructure and spending are main drivers[2].

- Falk, M., & Katz-Gerro, T. (2015). Cultural Participation in Europe: Common Determinants. Journal of Cultural Economics. Reviews many studies showing both positive and negative income effects: higher income often increases likelihood of attendance, but raises opportunity costs, sometimes reducing attendance frequency[3].

- Brook, O. (2010). Cultural Participation and Local Context. Reports that access to cultural amenities shapes attendance, implying policy can equalize participation across income groups[2].

- Additional sources on cultural attendance and income (e.g. McCarthy et al. 2004; Ateca-Amestoy 2008) reinforce that education and income usually raise arts consumption, but patterns vary by country and context.

[1] thesis.eur.nl

https://thesis.eur.nl/pub/32878/Groot-Jorien-de.pdf

[2] [3] Spatially Disaggregated Cultural Consumption: Empirical Evidence of Cultural Sustainability from Austria

https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/23/10023

Copyright & Good Faith Notice

This blog post is shared in good faith and for general informational and educational purposes only. The author does not intend to infringe upon any copyrights or intellectual property rights.

While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure proper attribution, some references, citations, or sources may be incomplete or unintentionally inaccurate. Any such issues are unintentional.

If you believe that any content in this post infringes upon your rights or has been used without appropriate credit, please contact the author. Upon notification, the content will be promptly reviewed and, if necessary, corrected, credited, or removed.