Eldar H. Mammadov

Abstract

Poverty is fundamentally conceptualized as a socio-economic condition in which individuals are unable to secure the essential resources required for basic subsistence. The perception of poverty is subject to both subjective interpretations and objective structural formations. This study aims to elucidate the ontological perception of poverty among household members in Azerbaijan and to evaluate their perspectives on current anti-poverty policy paradigms. Methodologically, a quantitative approach was employed via an online survey conducted with 105 participants. Empirical findings suggest that respondents do not attribute poverty to individual deficiencies; rather, they correlate its persistence with macro-economic determinants. Furthermore, there is a pervasive consensus that extant state-led programs lack sufficient efficacy and utility. These results provide critical normative data for governmental bodies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) focused on labor market dynamics, and scholars engaged in social welfare research.

Keywords: Poverty, Welfare Economics, Azerbaijan, Structural Unemployment

1. Introduction

The seminal definition of “poverty” was established in 1901 by Seebohm Rowntree, who posited that poverty emerges when an individual’s resources fall below the minimum threshold required for biological survival, specifically concerning nutrition, clothing, and shelter. However, in the contemporary economic discourse, it is analytically reductionist to associate poverty exclusively with malnutrition or caloric deficiency (Dumanlı, 1996: 2).

The global scale of deprivation remains an acute socio-economic crisis. Statistics indicate that approximately 100,000 individuals succumb daily to hunger and its associated complications. In the year 2000 alone, 36 million fatalities were recorded due to these systemic failures. Every six minutes, an individual suffers from irreversible vision loss due to vitamin A deficiency. Out of a global population of 6.2 billion (at the time of the reported data), 826 million endure chronic malnutrition and persistent food insecurity. Furthermore, 1 billion people lack access to potable water, while 2.4 billion are deprived of adequate sanitation facilities.

The gravity of the global disparity is further highlighted by the fact that 4 million people die annually from diarrheal diseases, and 1.1 million children in Africa are HIV-positive. There remains a staggering 25-year discrepancy in average life expectancy between the European and African continents. From a distributive justice perspective, it is a sobering reality that the global hunger crisis could potentially be mitigated by a sum equivalent to the annual expenditure on fragrances in the United States (US) and the European Union (EU). A comprehensive examination of these global realities underscores the critical and distressing nature of the problem (www.sosyalhizmetuzmani.org/).

Table 1: Longitudinal Analysis of Extreme Poverty by Region (Millions of people) (Source: World Bank, 2019)

| Region | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2015 | 2030 (Proj.) |

| East Asia and Pacific | 987 | 362 | 222 | 147 | 3 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 13 | 23 | 11 | 7 | 2 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 63 | 55 | 36 | 26 | 19 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 14 | 9 | 8 | 19 | 26 |

| South Asia | 536 | 510 | 401 | 216 | 50 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 278 | 388 | 408 | 413 | 416 |

The foundational causes of poverty are multifarious, encompassing regressive or inequitable taxation systems, exorbitant interest rates, institutional governance failures, and natural catastrophes. Furthermore, individual-level factors—such as a high prevalence of persons with disabilities, cognitive and capability disparities among individuals, market monopolization, erratic state subsidies, inflationary pressures, and structural unemployment—constitute significant drivers of economic deprivation (Aktan, 2002).

When isolated from demographic and social catalysts—such as rapid population growth, migration, urbanization, aging demographics, and systemic discrimination—or from geographical and political triggers like climate change, natural disasters, and armed conflicts, poverty is predominantly the outcome of disruptions in the fundamental economic fabric (Altan, 2004). The discourse on social justice is as primordial as the issue of distribution itself. Justice commences with the recognition of the imperative for equitable sharing. The most archaic legal frameworks were those regulating distribution, a concern that remains central to all movements prioritizing human welfare. Justice necessitates that every individual secures adequate nutrition while simultaneously ensuring that each person contributes to the collective productive output (Canetti, 1998: 189).

The determinants of poverty can be systematically categorized under the following thematic frameworks:

- Geographical Determinants: Scarcity of natural resources, lack of arable land, and restricted access to freshwater sources.

- Regional/Geopolitical Constraints: Economic blockades and marginalization from global trade corridors.

- Individual Attributes: Health disparities, human capital deficits, and variations in educational attainment.

- Socio-Political and Macroeconomic Factors: Inaccessibility of healthcare and educational services, labor market rigidities, cyclical economic crises, and limited access to low-interest credit facilities.

In the analytical classification of poverty, the distinction between absolute and relative poverty is paramount. Absolute poverty denotes a severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, and sanitation facilities, due to a lack of sufficient economic resources. The World Bank currently operationalizes the absolute poverty threshold as living on less than $1.25 per day (approximately 2.13 AZN). Conversely, relative poverty refers to a condition where individuals earn an income significantly lower than the median or socially acceptable standard within their specific societal context.

The Conceptualization of Poverty and Alleviation Policy Frameworks

Historically, poverty has constituted one of the most formidable challenges to human development. In contemporary discourse, the nexus between poverty and social welfare remains a paramount socio-economic concern.

The primary metrics utilized to operationalize the poverty threshold include:

- The headcount of the population with incomes below the subsistence minimum;

- The Poverty Headcount Ratio (the proportion of the impoverished population relative to the total population);

- Nominal and real per capita incomes of those residing below the poverty line, including segments with incomes below half of the median and mean income, as well as the 10th and 15th percentiles of the lowest-income cohorts;

- The index of temporal change in nominal and real per capita income among low-income households;

- The absolute and relative size of households experiencing negative income growth;

- The ratio of aggregate income to the subsistence minimum.

Poverty can be analyzed through several methodological prisms:

- Absolute Approach: Defined by levels falling below the subsistence minimum.

- Relative Approach: Defined by income levels below 60% of the median indicator.

- Subjective Approach: Evaluation of poverty through empirical population surveys.

- Qualitative Approach: Consideration of individuals’ actual standing within the production system, transcending mere income metrics.

- Integral Approach: A standardized composite indicator synthesizing various statistical characteristics that determine population poverty (Aytəkin Məmmədova, 2020).

Governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) continually implement interventions aimed at poverty alleviation and welfare enhancement. In the context of Azerbaijan, the “State Program on Poverty Reduction and Economic Development (2003-2005)” and the “State Program on Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development (2008-2015)” serve as primary examples. Based on these frameworks, nine strategic objectives were formulated:

- Ensuring sustainable economic growth through macroeconomic stability and the balanced development of the non-oil sector;

- Expanding income-generating opportunities and achieving a significant reduction in the headcount of the most impoverished strata;

- Developing the social protection system to mitigate social risks for the elderly, low-income families, and vulnerable groups;

- Continuing systematic interventions to improve the living conditions of refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs);

- Enhancing the quality of and ensuring equitable access to primary healthcare and educational services;

- Advancing social infrastructure and optimizing public utility systems;

- Improving environmental conditions and ensuring sustainable environmental governance;

- Promoting and protecting gender equality;

- Advancing institutional reforms and optimizing good governance (Asian Development Bank).

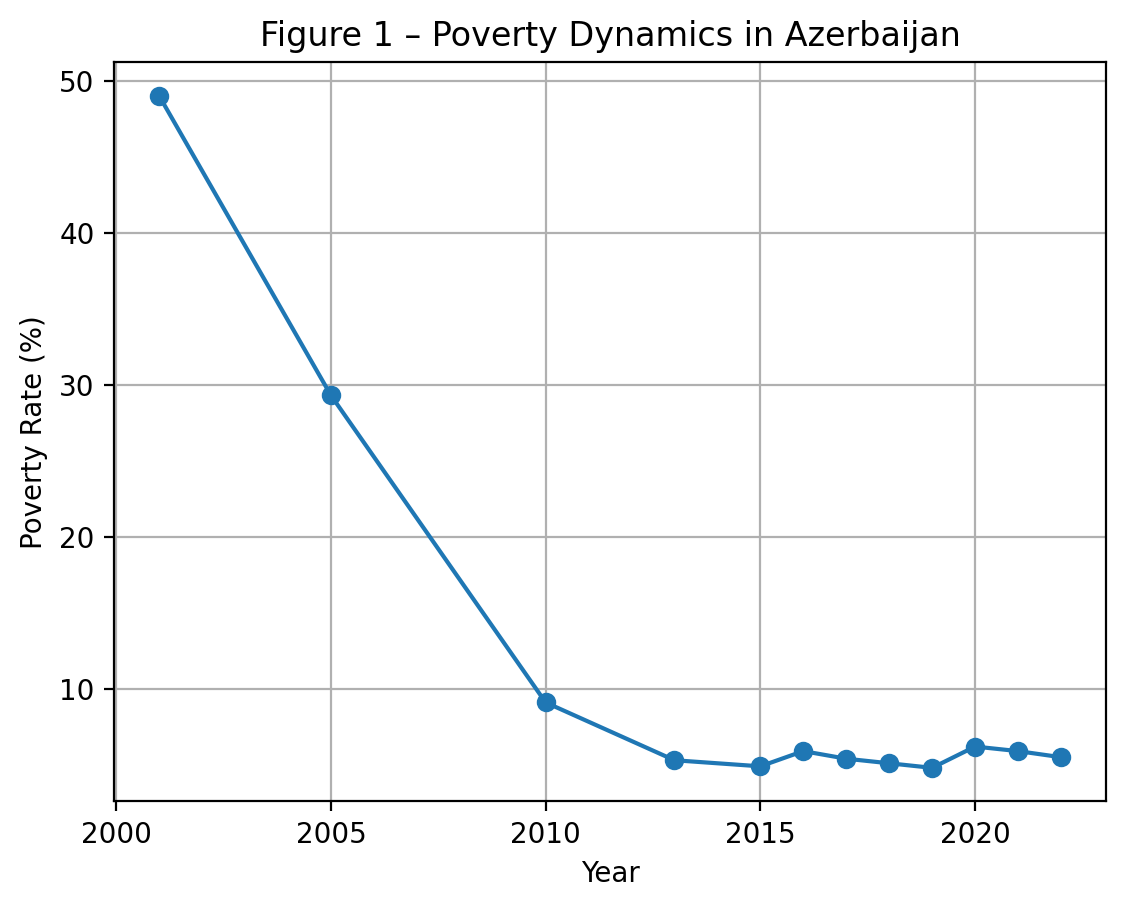

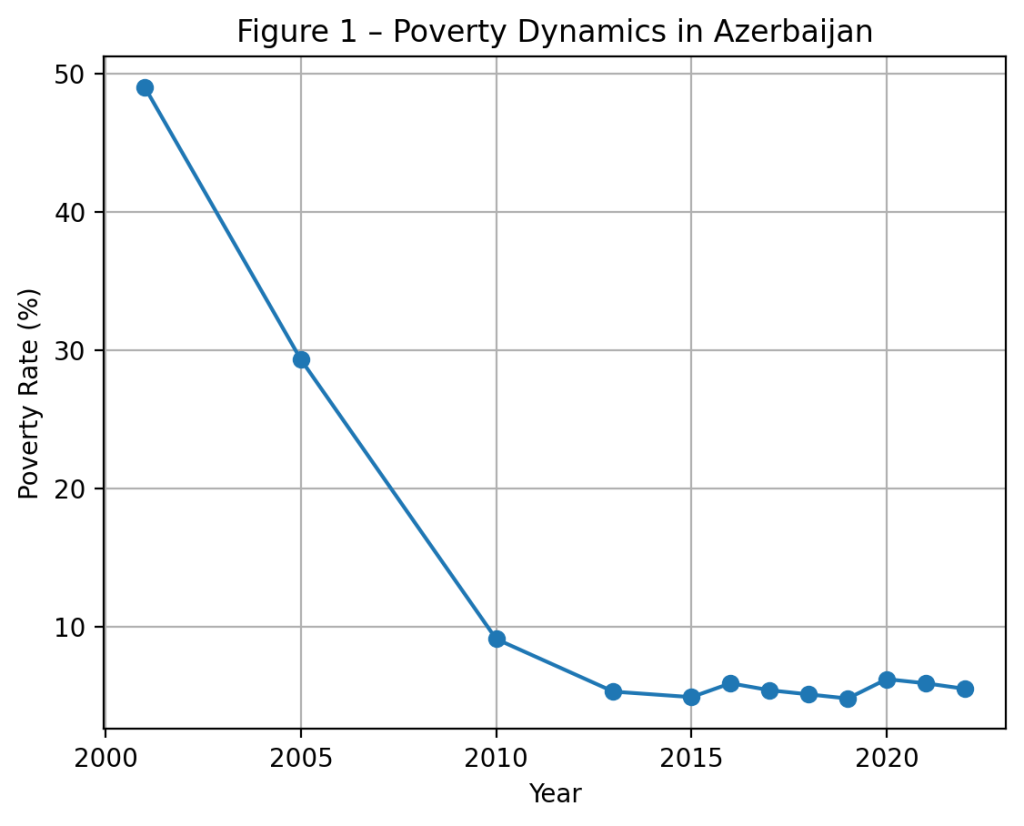

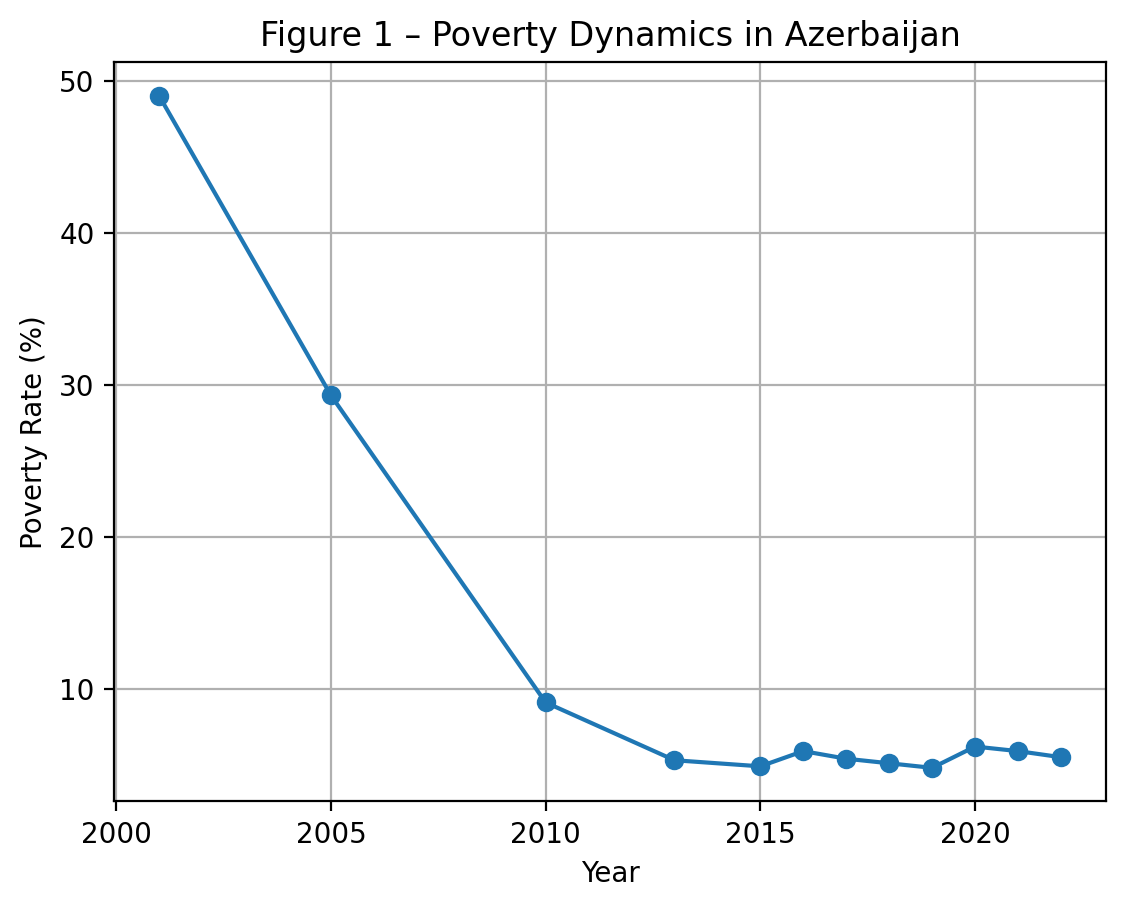

Poverty is not merely a static economic concept predicated on income deficits; it is an inherently political construct. Consequently, poverty eradication is established as the primary goal within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework. According to official data, the longitudinal trend of the poverty rate in Azerbaijan is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Poverty Dynamics in Azerbaijan (Source: State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan)

The poverty threshold in Azerbaijan has undergone significant nominal shifts, recorded at 42.6 AZN in 2005, 135.6 AZN in 2015, and reaching 229.6 AZN by 2022. While official longitudinal data reflects a downward trajectory in the poverty headcount ratio, the risk of sudden impoverishment remains a critical concern, as unforeseen natural or economic shocks could potentially expose over half the population to poverty. This vulnerability is primarily driven by systemic issues such as structural economic fragility, high import dependence, lack of economic diversification, and the excessive centralization of financial resources. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the risk of pauperization is disproportionately higher among specific cohorts:

- Residents of rural regions and peripheral settlements;

- Large-scale household units;

- Demographic groups aged 1–15 and elderly individuals aged 50 and above;

- Families categorized as refugees or Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs);

- Individuals with lower levels of educational attainment.

Minimizing poverty remains a core strategic objective for states, as it acts as a catalyst for socio-legal pathologies, including exploitation, forced illicit activities, human trafficking, increased criminality, and the expansion of informal employment. Beyond the poverty line, the state establishes “subsistence minimum” and “minimum wage” benchmarks to regulate social welfare. The Azerbaijani government defines poverty as a “large-scale challenge transcending economics to include social and institutional dimensions” (State Program on Poverty Reduction 2008–2015). In Azerbaijan, welfare is operationalized via per capita consumption expenditure, where the subsistence minimum is calculated based on a consumer basket—70% of which comprises food items—ensuring a daily intake of 2,420 kilocalories (Maşallı T., 2022).

2. Problem Statement

Azerbaijan has achieved substantive statistical progress through frameworks such as the “State Program on Poverty Reduction and Economic Development (2003–2005),” the 2008–2015 sustainable development program, and the “Azerbaijan 2020: Look into the Future” vision. Consequently, the poverty rate plummeted from 49% in 2001 to 5.5% in 2022. However, it is analytically imperative to note that this transition was primarily fueled by burgeoning hydrocarbon revenues rather than endogenous economic diversification.

Azerbaijan serves as a quintessential case study of an oil-dependent economy. Preliminary data for 2022 indicates that the oil and gas sector generated 47.8% of the GDP, accounted for 52.7% of budget revenues, and constituted a staggering 92.5% of total exports. Despite minor fluctuations since 2005, this rentier-state trend remains static (İnqilab Əhmədov, 2023). While large segments of the population have been lifted out of absolute poverty, a significant number of citizens reside in the “precarious” zone—just above or below the poverty threshold. These groups suffer from underemployment or structural unemployment and remain exceptionally vulnerable to exogenous shocks (Asian Development Bank).While poverty is defined as a deprivation of the essential requirements for human subsistence, the “perception of poverty” is a cognitive process involving the interpretation of sensory inputs—reaching the brain through the nervous system via environmental interaction—by ascribing personal meanings to them (Noë, 2003:95). Consequently, it can be argued that the concept of poverty, much like the phenomenon itself, lacks a singular, monolithic definition; rather, it represents a cognitive effort by individuals to comprehend the condition of deprivation.

In a general sense, household members perceive poverty through three distinct analytical lenses. The first perspective posits that individuals bear personal responsibility for their impoverished state. The second perspective suggests that macro-level economic, political, and cultural issues are influential in shaping the perception of poverty. The third perspective is based on a fatalistic view, where poverty is perceived as an inevitable consequence of illness, disability, or misfortune. While individualistic and fatalistic approaches can be addressed through subjective assessment, the dependence of poverty on socio-economic problems and the influence of political factors must be resolved via objective evaluation (Shek, 2004:273). Poverty assessments conducted through objective processes encompass structural problems, such as social injustice (i.e., lack of social opportunities), economic inequality, resource scarcity, and the political conceptualization of poverty. Within objective assessments, individuals recognize that the problem of poverty stems from structural deficiencies rather than personal attitudes, as they lack the agency to manipulate macro-factors such as unemployment, inflation, and aggregate employment levels.

3. Research Objectives and Methodology

Given that poverty is a multidimensional construct that varies across time, space, and individual circumstances, measuring it through objective methods based on income or expenditure—alongside subjective methodologies—ensures a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. The primary objective of this study is to examine the perception of poverty among household individuals in Azerbaijan and their attitudes toward poverty alleviation policies.

The research utilized an online survey methodology. A total of 105 respondents participated in the study, answering 12 questions, two of which were open-ended. Due to resource constraints during the research period, it was not possible to reach a more extensive sample size.

The respondent cohort consists of 56% male and 44% female participants. To ensure a nuanced analysis across different life stages, the sample was stratified into three primary age groups:

- 16–24 years: 33 participants;

- 25–35 years: 52 participants;

- 36–65 years: 20 participants.

Regarding professional engagement and labor market status, the respondents were categorized as follows:

- Private Sector Employees: 46 individuals;

- Unemployed: 32 individuals;

- Public Sector Employees: 18 individuals;

- Entrepreneurs: 4 individuals;

- Other: 5 individuals.

4. Empirical Findings and Data Analysis

The quantitative data derived from the survey instrument provides critical insights into the public perception of poverty and the perceived efficacy of institutional interventions. The responses to the structured questions (based on a 5-point Likert scale) are summarized below:

Table 2: Quantitative Survey Results (n=105)

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Undecided | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

| Q1. Poverty is a socio-economic problem observed directly or indirectly in our society. | 56 | 38 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Q2. Individuals bear more responsibility for poverty than the shifting dynamics of the national economy. | 6 | 9 | 28 | 47 | 15 |

| Q3. The risk of impoverishment in regions is lower than in major metropolitan areas. | 6 | 26 | 24 | 33 | 16 |

| Q4. Personal initiative is sufficient to escape poverty; direct state intervention is not required. | 2 | 9 | 6 | 51 | 37 |

| Q5. It is possible to completely eradicate poverty in Azerbaijan through specific programs and projects. | 8 | 38 | 34 | 18 | 7 |

| Q6. I consider the efforts of institutions working to reduce poverty and unemployment in Azerbaijan to be sufficient. | 1 | 2 | 12 | 48 | 42 |

4.1. Qualitative Analysis of Open-Ended Responses

Q7. What are the primary challenges and obstacles faced by individuals attempting to overcome poverty?

Since this was an open-ended inquiry, the qualitative responses were categorized into thematic clusters. The predominant themes identified by the respondents include:

- Regional Labor Market Deficits: Scarcity of employment opportunities in peripheral regions.

- Aggregate Unemployment: General lack of available job positions.

- Institutional Barriers: Absence of a conducive and favorable business environment.

- Policy Inconsistency: Lack of sustainability and realism in social projects, alongside insufficient regional coverage.

- Governance Issues: Systemic corruption.

Q8. Have you encountered the risk of impoverishment in your personal life?

The qualitative synthesis of the responses reveals a concerning trend: a significant majority of the respondents reported having personally experienced the risk or reality of poverty at some stage in their lives

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Poverty is a multidimensional phenomenon that lacks a singular, precise definition but manifests ubiquitously as a consequence of socio-economic inadequacies. While historically conceptualized through the narrow lens of income and expenditure, contemporary discourse recognizes poverty as an aggregate of deprivations, including restricted access to education and healthcare, systemic social exclusion, and chronic economic insecurity.

Given its multifaceted nature, the perception of poverty varies significantly across individual and societal contexts. The integration of subjective and objective assessments is critical, as the perception of poverty directly informs the conceptualization and implementation of effective alleviation strategies. The empirical findings of the study, “Household Perceptions of Poverty and Attitudes Toward Anti-Poverty Policies in Azerbaijan,” can be synthesized as follows:

- Discrepancy in Statistical Reporting: Despite low official poverty rates, survey data suggests that alternative methodologies might yield divergent results. Respondents, as active societal agents, observe and encounter poverty in diverse forms; notably, 89% of participants acknowledged poverty as a pervasive socio-economic challenge.

- Structural vs. Individual Causality: There is a pronounced tendency to attribute poverty to macro-structural economic conditions rather than individual failure, with 69% of respondents favoring this perspective. Although 85% of respondents are aged 16–35 and did not experience the Soviet era, the legacy of a seventy-year socialist regime and intergenerational influence may shape this structural worldview. Open-ended responses further underscored this by citing a lack of state-led job creation and strategic labor specialization. Furthermore, lower living standards compared to other oil-rich nations exacerbate this perception.

- Regional Disparities: Household members perceive the risk of impoverishment in regions to be at least as severe as in metropolitan centers. This is primarily attributed to the significant deficit of employment opportunities in rural areas and the excessive concentration of national wealth within the Absheron Peninsula.

- Institutional Trust and Efficacy: The study reveals a significant deficit in institutional trust. While 44% of respondents believe in the potential of state programs, 32% remain skeptical, indicating low confidence in current implementation strategies. A staggering 86% of respondents characterized the performance of agencies responsible for employment and poverty reduction as insufficient. Criticisms specifically targeted the State Employment Agency (DMA) for its perceived ineffectiveness, with qualitative responses referencing widely reported instances of substandard support, such as the provision of diseased livestock under self-employment programs. These findings suggest that the lack of public participation and social dialogue in policy design undermines the efficacy of such interventions.

5.1. Policy Recommendations

To enhance the efficacy of poverty alleviation frameworks in Azerbaijan, the following strategic interventions are proposed:

- Data Optimization: Addressing existing lacunae in the national poverty database is a prerequisite for evidence-based policymaking.

- Universal Access: Ensuring equitable access to high-quality education and healthcare services across all demographics.

- Microfinance Frameworks: Developing a robust national strategy for micro-financing to empower low-income entrepreneurs.

- Inclusive Policy Design: Integrating the principles of public participation and community engagement in the formulation of employment programs to ensure that the voices of those affected are integrated into the decision-making process.

- Formal Labor Market Incentivization: Investigating and mitigating the factors that drive labor into the informal sector to make formal employment more attractive and secure.

- Regional Tailoring: Incorporating local community feedback and specific regional socio-economic conditions into the design of regional development initiatives.

5.2. Research Limitations and Directions for Future Study

The primary limitation of this research was the constraint on resources, which restricted the sample size. Furthermore, the scarcity of contemporary academic literature analyzing poverty perceptions in Azerbaijan presented a contextual challenge. Future research would benefit from a focus group methodology involving diverse societal strata to mitigate the potential demographic bias inherent in online surveys. Despite these limitations, this study provides an essential preliminary analysis of how household individuals in Azerbaijan perceive poverty and the institutional efforts to combat it.

References

- Aktan, C. C. (2002). Gelir Dağılımında Adaletsizlik ve Gelir Eşitsizliği: Terminoloji, Temel Kavramlar ve Ölçüm Yöntemleri, Yoksullukla Mücadele Stratejileri [Injustice in Income Distribution and Income Inequality: Terminology, Basic Concepts and Measurement Methods, Poverty Alleviation Strategies]. Ankara: Hak-İş Konfederasyonu Publications, pp. 1-21.

- Altan, Ö. Z. (2004). Sosyal Politika Dersleri [Social Policy Lectures]. Eskişehir: Anadolu University Publications.

- Asian Development Bank. (2014). Country Partnership Strategy: Azerbaijan, 2014–2018. Available at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/cps-aze-2014-2018-pa-az.pdf.

- Canetti, E. (1998). Kitle ve İktidar [Crowds and Power]. Translated by Gülşat Aygen. Istanbul: Ayrıntı Publications, p. 189.

- Dumanlı, R. (1996). Yoksulluk ve Türkiye’deki Boyutları [Poverty and its Dimensions in Turkey]. State Planning Organization (DPT) Expertise Thesis, Publication No: 2449, Ankara, p. 2.

- Əhmədov, İ. (2023). Azərbaycanın daimi mühərriki – neft [Azerbaijan’s permanent engine – oil]. Baku Research Institute. Available at: https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/azerbaycanin-daimi-muherriki-neft/.

- Gümüş, B. (2023). Türleri, Nedenleri ve Boyutlarıyla Türkiye’de ve Dünya’da Yoksulluk Sorunu [The Problem of Poverty in Turkey and the World with its Types, Causes, and Dimensions]. Journal of Necmettin Erbakan University Faculty of Political Sciences, Konya.

- Mammadova, A. (2020). Azərbaycanda yoxsulluğa səbəb olan amillər və onların aradan qaldırılması yolları [Factors causing poverty in Azerbaijan and ways to eliminate them]. SSRN. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3607123.

- Maşallı, T. (2022). Azərbaycanda yoxsullar və işsizlər [The poor and unemployed in Azerbaijan]. Baku Research Institute. Available at: https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/the-poor-and-unemployed-in-azerbaijan/.

- Noë, A. (2003). Causation and perception: The puzzle unraveled. Analysis, 63(2), pp. 93-100.

- Republic of Azerbaijan. (2008). Presidential Decree on the approval of the “State Program on Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development in the Republic of Azerbaijan for 2008-2015”. Available at: http://www.e-qanun.az/framework/15399.

- Shek, D. T. (2004). Beliefs about the causes of poverty in parents and adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 165(3), pp. 272-292.

- State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Millennium Development Goals. Official website. Available at: https://www.stat.gov.az/source/millennium/.

- The Social Work Expert Website. (n.d.). World Poverty Realities. Available at: www.sosyalhizmetuzmani.org/.

- World Bank. (2019). Extreme Poverty by Region. Global Poverty Monitoring Database.

Household Perception of Poverty and Attitudes Toward Anti-Poverty Policies in Azerbaijan

-

Household Perception of Poverty and Attitudes Toward Anti-Poverty Policies in Azerbaijan